Some references and thoughts on topics I have given workshops on: procrastination, the impostor phenomenon, the growth mindset, abstract writing, presenting, and post-PhD tips. As a bonus, you can find my list of essential fieldwork packing.

How to (not) Procrastinate

More people than you think display procrastination behaviour, i.e. putting off a task that we know needs to be done, even if delaying it will likely make it worse. If this is bothering you, there is a wealth of blogs to be found on the subject, but you could also have a look at one of the following books – I especially recommend Tim Pychyl’s little guide:

- Sapadin, L. 2012. How to beat procrastination in the digital age. PsychWisdom Publishing.

- Burka, J.B., Yuen, L.M. 1983. Procrastination: why you do it and what to do about it now. Perseus Books, Reading, Massachusetts. → second edition 2008!

- Ferrari, J. R. 2010. Still Procrastinating? The No Regrets Guide to Getting It Done. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

- Pychyl, T. A. 2013. Solving the procrastination puzzle. Tarcher.

- Sapadin, L. with J. Maguire. It’s about time. 1996. The six styles of procrastination and how to overcome them. Penguin Books. → new 2020 edition for college students!

Tim Pychyl’s procrastination lab also produces podcasts on this topic, which explain the science behind procrastination. Another insightful overview is on the website Solving procrastination. There is also this funny and insightful explanation, and just for fun, this field guide to types of procrastinators.

The opposite, precrastination, can also hinder you. It is “the tendency to tackle subgoals at the earliest opportunity — even at the expense of extra effort”. This NYT article on ‘the early bird‘ explains how.

The impostor phenomenon

If you’re feeling like a fraud, find that you don’t belong in the academic world, or think you’re not good enough and going to be found out, you might identify with what is described as the ‘impostor phenomenon’. Academics struggle with this more often than the average population, because most of the time, our task is to look at what we do not know yet! It’s equally common for men and women in academia. There are tons of information and help to be found about this on the internet, but my best advice would be: read the book ‘The secret thoughts of successful women’ by Valerie Young. Just buy it and read it.

Otherwise, these were the posts I found clearest and most helpful:

Geek Feminism

How graduate students can fight the impostor syndrome (Inside Higher Ed)

Unmasking the impostor (NatureJobs.com)

Further reflection, and how women of colour might experience the inverse can be found in this insightful article in the New Yorker: Why everyone feels like they’re faking it.

And some fun charts, just to laugh about your own thoughts!

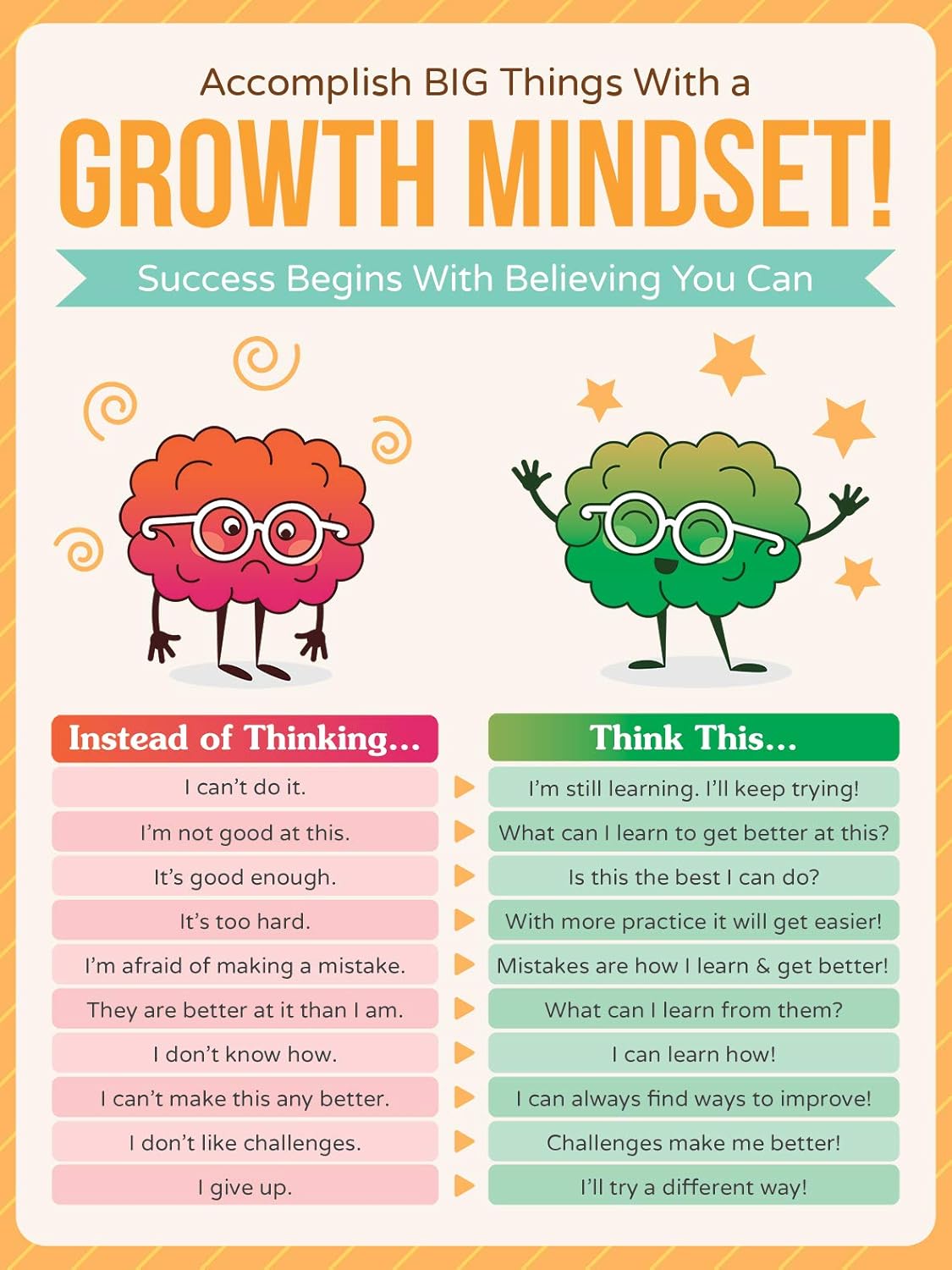

Growth mindset

Dr. Carol Dweck described a difference between a mindset in which intelligence or personality is something that can grow, as opposed to believing there is a fixed set of talents or traits. The growth mindset is generally more helpful, especially in the challenging and creative environment of academia. Here is a little video explaining the mindsets.

Abstract writing

It is important to get your thoughts on paper in a clear, convincing and concise way, in order to interest readers and get accepted into conferences. Here are some top tips for how to do it:

Johan Rooryck & Vincent van Heuven’s tips for abstract writing

LSA model abstracts

Maggie Tallerman’s advice

Presenting

The first step of giving an excellent presentation is asking yourself why you give that presentation. What is your goal? Do you want to get feedback on your ideas? Then give a ‘questions’ talk and invite the audience to help. Do you want to persuade people? Then give an ‘answers’ talk and potentially trigger the audience to challenge you. Or perhaps you want to mainly present yourself, for example in a job talk.

A second step asks the question ‘to beam or not to beam?’ – what visual aid best supports your story? A handout? Slides? (Or perhaps nothing at all? I’ve seen Paul Newman tell a crystal clear and fascinating research story with just him standing there!).

And for all the rest, you can find top tips here.

Post-PhD tips

You’ve finished you’re PhD – congratulations! And now what? An academic career? If so, how to go about it and what to expect? Here are some things that I learned:

- Is this for you? Before anything else, you want to have a good long conversation with yourself and someone who knows you (and your work) about whether you are fit for an academic career. Is your research good enough to find a job at a university or research institute? Furthermore, doing research is amazing, but academia comes with lots of other tasks: applying for grants, teaching, supervising students, reviewing papers, project management, etc. Is the whole package appealing enough?

- Set a period. If you feel like giving up and all the postdoc and lecturer applications are not working our, set a realistic period for yourself during which you keep trying for an academic career. If by the end of the two years, for example, you have not managed an academic position, then you stop trying and find another job. But equally, if during those two years you feel like quitting, you have promised yourself you’ll keep trying. This way, you do not have to wonder and doubt during the set period: you have taken your decision to keep trying during this period. And hopefully something comes along before the end!

- First research, then teaching. Although a better balance is being established between appreciation for research and teaching (and outreach), having a strong research profile is still considered very important. If you have your research output, people are typically willing to believe that you can also teach about the topic, whereas the other way around is less likely. Doing a post-doc may therefore be more beneficial in the long run than accepting a teaching position.

- Choose your area. You can either choose your geographical area or your professional area, but hardly ever both. If you want to stay in Germany, you must be flexible in applying for postdocs in various areas of linguistics; if you want to do formal syntax, then you must be flexible in where you will do it and ready to move to another country.

- Find a mentor. If you have chosen to pursue a career in academia, there will be many opportunities and choices to make. Is it worthwhile applying for this grant? How can I find collaborators? Should I become an editor of this journal? It is helpful in those cases to have someone by your side who is more experienced than you and who knows the area you are working in. Ideally, this mentor is not in the same institute, so that they can really be there for you and have your best interest at heart (rather than also the interest of the institute).

- Grant-writing is a skill. Practice with it and ask for help early. This is a typical area of ‘pay it forward’: the ones who are successful in obtaining project money have been helped by many other people, and to appreciate the help they received, they should offer their insights and feedback to the applicants in the next generation. So when you’re writing a grant proposal, go ahead and ask for examples of applications or enquire if they can read through yours.

- Pay it forward. Once you’re in a position that gives you some breathing space, use that space to help the next generation. See the previous point, but also in asking juniors to co-supervise with you, do reviews (together), mention their names for roles that may benefit them, finding money to hire them, offer your insights and access to your network.

fieldwork

I’ve put together a list of stuff I bring on fieldwork, ranging from ‘official stuff’ to ‘resilience stuff’ to ‘handy stuff’. Here it is.

MS word

If you’re using Word to write your papers, here are two amateur videos explaining how to automatically number your examples and reference to them, and how to align your examples.